The American 'Oppenheimer' Belongs to Irishman Cillian Murphy

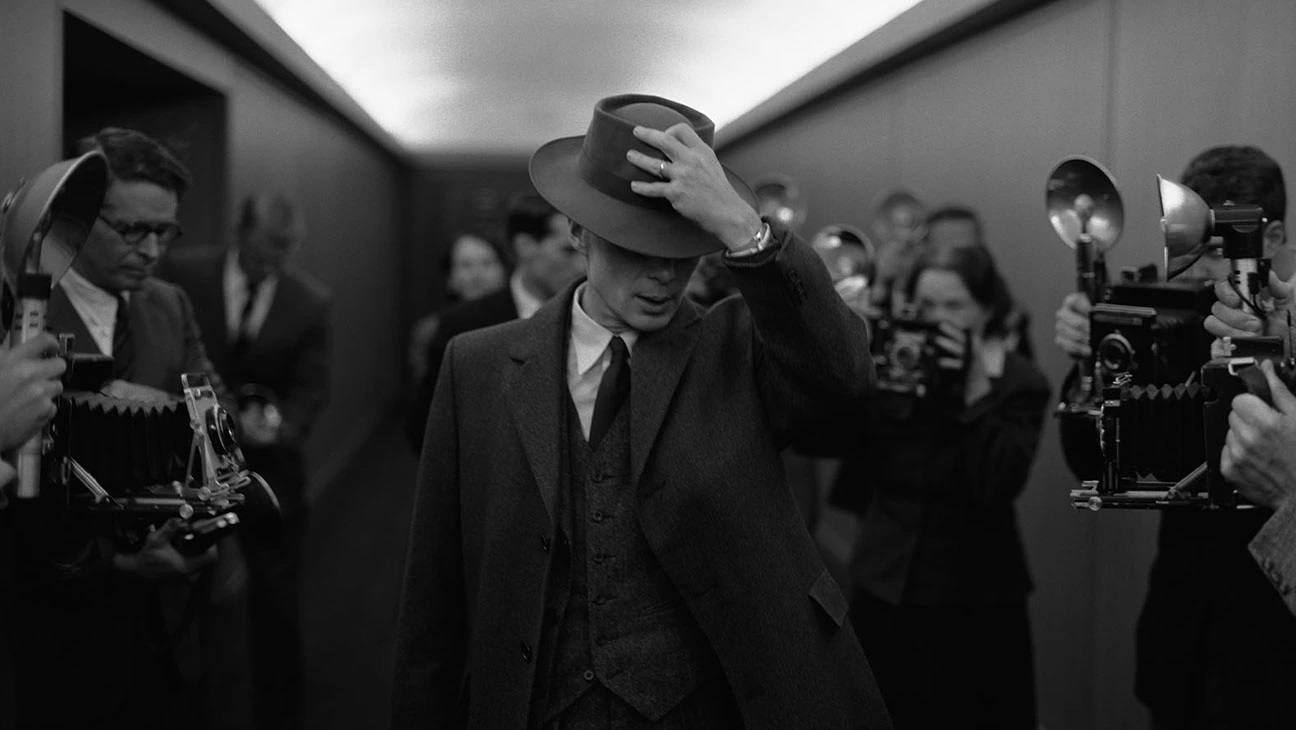

Cillian Murphy as Robert Oppenheimer in 'Oppenheimer'

Universal Pictures

You could argue that post-war America, having gained the ability to obliterate entire sovereign nations, elected to focus its power on killing itself. The dogmatic conservative values, the ruthless Cold War paranoia, and the constant dog-piling on its nation’s most creative and radical thinkers (not to mention its militarized bigotry) made the 1950s a period where the United States was fixated on poisoning whoever it decided was a threat. Such a vague and nebulous threat makes the many motives of personal vindictiveness transparent to generations looking back today.

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, a biopic about the father of the atomic bomb, clearly doesn’t argue that everyone caught up in the political machinations of the first half of the 20th century deserves our deepest sympathies or even absolution. It does, however, convey the reactive, uncontrolled testing ground for latter-day American moral rot — and how easy it was for people to create the conditions of their own insanity.

Irishman Cillian Murphy (Peaky Blinders) has appeared in six Nolan films, with Oppenheimer marking his first lead role. It’s almost like Nolan has had to shift his filmmaking around the talents of his leading man; a detailed, talky drama that (mostly) deserts spectacle for thorny, challenging psychology, where the IMAX cameras that film every single scene are solely interested in capturing the twitches and anxiety lines of our ensemble’s faces. That’s not to say Oppenheimer isn’t cinematic — in one of Nolan’s most visually impressive efforts yet (in Hoyte van Hoytema we trust), the director levels up his impressive command of blocking, sound, and editing to awe and amaze in more piercing and confronting ways than we saw in Gotham’s cityscape or worlds of inverted time.

For those still in the dark, Oppenheimer is a film about the man, not the bomb. There’s more of Dunkirk’s intentionally choppy timeline, but it’s streamlined and easier to digest thanks to slick, clean work from editor Jennifer Lame. Her structural and momentary edits adhere to a robust momentum while leaning into more impressionistic flairs as the bomb nears detonation and we’re left with the sickening aftermath. Plus, in suitably blunt Nolan fashion, we shift between gorgeous 70mm color and crisp black-and-white to denote, according to the director, the subjective memories of Oppenheimer and the austere outsider perspective that came after him post-Hiroshima.

Never has a Nolan film belonged more to its star, maybe because no prior Nolan film has ever been named after its lead character (I’m talking Christian names here, Batman doesn’t count). Murphy has a mammoth task and makes a titanic effort with the tense fluctuations of power and influence the scientist experienced throughout his life. A disaffected and outsider physicist prone to irregular and alarming behavior even as a young man, Robert J. Oppenheimer only started to find his place in scientific academia when radical Jewish thinkers became extremely unwelcome in continental Europe and when anti-leftwing surveillance took flight in America.

To say Oppenheimer flirted with American communism would be over-generous — it seemed there was nobody in his pre-Manhattan Project life who wasn’t connected to the movement in some way. But how were citizens in the 30s to know that any leftist curiosity or fraternization would be later used against them in the most prejudicial terms? Oppenheimer’s political context is crucial to understanding his methods of asserting control over his life and work and why it wasn’t until too late did he realize his scientific zeal had been appropriated for something stomach-turning.

The Nazis, Japanese, or Soviets make no appearance in Oppenheimer; a choice made more resonant when you realize that the pressure to create and use the atom bomb came from generals and politicians insisting on the danger of threats that we, and the characters, don’t see. It’s a subversion of the classic rule of “show, don’t tell” – by opting for the less dramatically convincing “tell,” Nolan wants us to consider that it maybe wasn’t the most necessary thing in the world for the US army to wield that much destructive power against Japan in August 1945.

Oppenheimer is a crowded film, with many surprise faces in the cast relegated to one noteworthy scene each (largely the young ’uns — Jack Quaid, Josh Peck, Alex Wolff). Strangely, the two women in Oppenheimer’s life also feel sidelined, even if Nolan’s script works hard to stress how defining these relationships were for the unstable physicist, and actors Florence Pugh and Emily Blunt do brilliant work making every moment count. Some of the few performers who feel evenly matched with Murphy’s commanding presence are those capable of standing up to him: Matt Damon’s stern, gruff General Groves and Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss, the ultimate architect of Oppenheimer’s downfall.

It’s reductive to summarise Oppenheimer’s story: "Man changes the scientific world, goes crazy in the process.” If anything, science is the only thing that makes sense to Oppenheimer; how it’s used and how he’s punished for speaking out pushes him into further instability. But any scientific breakthrough of this magnitude will alter a human being on a fundamental level, something that a committed storyteller like Nolan, who’s invested in the ways cinema can manipulate or heighten a perspective, is eager to dive into. This culminates in several jaw-dropping scenes where we’re asked to consider the idea that knowledge, in specific contexts, can be cursed, and human beings are just not built to withstand the psychological burden that comes with it. It’s a horrible, upsetting idea to be left with. Oppenheimer isn’t interested in consoling us. Sit back, look at the pretty lights, and try convincing yourself it’s not the end of the world.

Oppenheimer opens in theaters worldwide Friday, July 21, 2023.