'Wolf Hall: The Mirror & the Light's' Timely Return Sets Pride Before a Fall

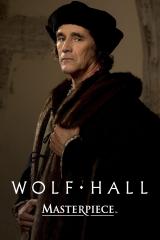

Mark Rylance and Damian Lewis in "Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light"

(Photo: Masterpiece)

It's been a decade since Wolf Hall first graced our screens. In the intervening years, we've seen plenty of takes on Tudor England, from the somewhat faithful (Becoming Elizabeth) to the stridently feminist (The White Princess, The Spanish Princess, Firebrand) and the downright fantastical (My Lady Jane). But while most of them have been enjoyable, none have reached the prestigious heights of the BBC's award-winning tale of Thomas Cromwell, which becomes glaringly apparent within the first moments of the sequel series Wolf Hall: The Mirror & the Light. The long-awaited adaptation of the final novel in Hilary Mantel's award-winning trilogy bristles with menace and horror; each scene feels as though it's balanced on a knife's edge.

Mantel's story is clear-eyed about the monstrousness of many of the men at its center, but in case you've forgotten, the premiere opens with a reasonably brutal reminder. We revisit scenes from the first series, forced to watch all over again as Claire Foy's tremulously terrified Anne Boleyn mounts the scaffold. This time, scenes featuring her quaking with fear are interspersed with her husband lazily dressing for the wedding planned for the woman who will replace her. (In real life, King Henry VIII married Jane Seymour around ten days after Anne's execution, but for dramatic purposes, this works better.) The casual cruelty of it all is stunning, as Henry is draped in glittering gold and presented with a quietly proper Jane just as his previous wife's now-headless body is packed into a crate.

Thomas Cromwell is there for it all, quietly watching the destruction of the woman he helped raise to the throne before turning on his heel, changing his clothes, and making his way to the celebratory festivities at Hampton Court, where he is rewarded for orchestrating a queen's murder with the fancy new title of Lord Privy Seal.

To talk about any iteration of Wolf Hall is to talk about Mark Rylance and the titanic performance that holds this franchise together. His interpretation of Thomas Cromwell often feels as slippery and mysterious as the real man often seems to us in history, and his performance contains multitudes. Suggesting everything but answering nothing, he runs the gamut from a loyal enforcer of Henry's whims to the unlikely protector of the currently disfavored Princess Mary, but every hat (both literally and figuratively speaking) is simply another mask he wears.

The Mirror and the Light gives us something that at least feels like a glimpse into Cromwell's inner psyche, thanks to a handful of scenes in which his inner monologue is made external through an apparition of Jonathan Pryce's Cardinal Wolsey. Since the real Archbishop of York is several years dead by the series' current moment of 1536, this Wolsey is one part memory and one part projection, a vision that the show uses to give its audience some much-needed insight into where Cromwell's head's at regarding many topics.

Unlike his public persona as the king's attack dog, in the darkness of his study, Cromwell is wry and thoughtful, aware of the precarious situation he (and England!) finds himself in now that he has essentially given Henry absolute power. Of course, Rylance looks every day of the decade-long gap between the first series of Wolf Hall and this one; his Cromwell has, in many ways, broken the world. From orchestrating England's abandonment of Rome, elevating the king to a position in which none can gainsay him, and essentially ending the lives of two innocent women in the process, he has almost certainly earned every line and gray hair.

If anything, Damian Lewis's Henry has become even more tyrannical in the wake of such a total and complete victory. He's rid of Anne, he's married Jane, and he's convinced he'll have a son any day now. With his takeover of the church, he literally answers to no one for his actions anymore, not even God. (Or, at least, I think we can safely assume that Henry's God will automatically approve of anything he does.)

All things considered, the premiere is fairly slow-moving and primarily focused on the fate of the king's eldest daughter, Mary. Declared illegitimate when Elizabeth was born, Mary's been stripped of the title of princess, removed from the line of succession, and forced to live a life of virtual imprisonment at Hunsdon House, all because her father is afraid that Catholics will somehow rally around her. Henry is determined that Mary should swear the oath recognizing him as head of the Church of England, no matter her religious loyalty to Rome and the Pope, and becomes increasingly unhinged every time it's hinted that she might not actually wish to deny a core tenant of her faith in the name of pleasing a madman.

Henry is not only paranoid about Mary's refusal to bend the knee to his paternal wishes but also furious that the prominent Pole family is both unapologetically Catholic and openly supportive of his daughter's claim to the throne. Lady Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury and the last surviving Plantagenet princess, was a longtime friend of Catherine of Aragon's and served as Mary's governess in her youth. Her son Reginald de la Pole, a scholar living in exile in France who is also the future Archbishop of Canterbury, has become particularly outspoken on Henry's marriage. He wrote a fairly hefty treatise (Pro ecclesiasticae unitatis defensione) on the subject and even went so far as to encourage the other princes of Europe to depose the king if he did not return to the faith.

Mary, for her part, is young and stubborn, but Cromwell is determined to save her life, thanks in part to the dangerous promise to protect her that he made to her mother in the last series. This involves essentially bullying her into signing a document that formalizes her status as a bastard. However, the ever-sneaky courtier insists that Mary can deny it all later if necessary (as long as she doesn't read what she's signing). Mary (portrayed with aching complexity by Lilit Lesser) eventually gives in and is restored to her father's side, handing Cromwell yet another win in the eyes of the king.

Despite his myriad successes, the specter of his doom dogs Cromwell throughout this episode. Henry is suspicious of his support for Mary, impatient about the status of the loyalty oath among his courtiers, and generally drunk with power in a way that can only feel foreboding. Cromwell himself seems well aware of the precariousness of his situation (ask John Fisher, Thomas More, Thomas Wolsey, or Anne Boleyn what happens when a king's favor turns), yet can't seem to help himself when it comes to throwing his weight around with the other nobles at court.

As the show rightly points out, Cromwell doesn't have a powerful family or loyal retainers to back him up or protect him should one of his plans go awry. While he seems to have no compunction regarding groveling at Henry's feet, a time is certainly coming when his go-to moves won't work anymore. (For those keeping track at home, it's in about four years.)

Wolf Hall: The Mirror & the Light airs on most local PBS stations and streams on the PBS app weekly on Sundays at 9 p.m. ET. All episodes are available for PBS Passport members and the PBS Masterpiece Prime Video Channel to binge before their on-air broadcast.