Netflix's Self-Centered 'Joy' Fails to Spark Joy

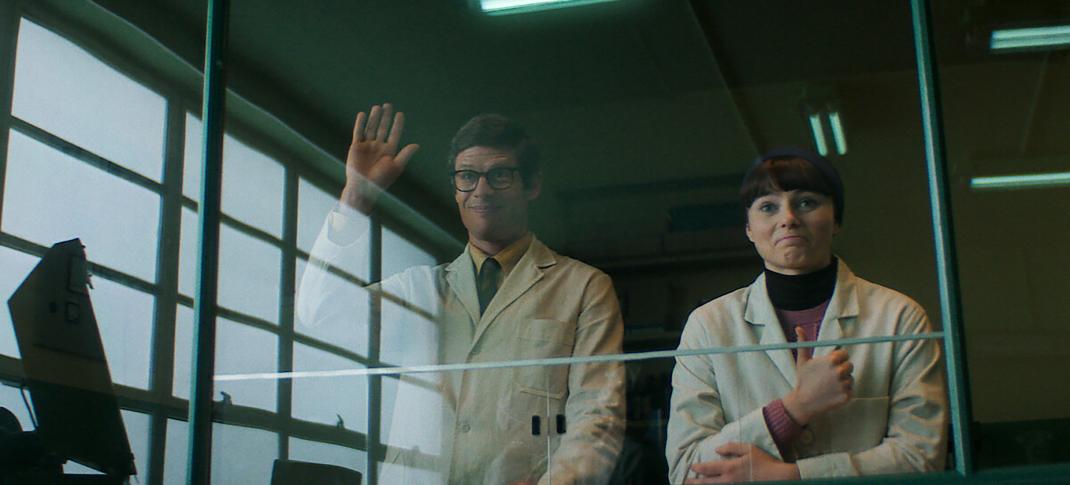

James Norton as Robert Edwards, Thomasin McKenzie as Jean Purdy in 'Joy'

Netflix

The political overtones of Joy, the biopic of the English scientists who pioneered in vitro fertilization births (IVF), are even more blatant the month it releases on Netflix. This November’s election has spread nationwide the fear that reproductive rights in America will enter a new dark age, but threats of abortion bans and evangelical policies didn’t come out of a vacuum – the same desires to quash the bodily autonomy of anyone who’s not a cisgender man have dominated conservative politics for centuries.

But although the film may be timely, the extent to which Joy can be enriched by resonance with the real-world context is more limited than it would like to believe. This is because Joy, which stars Thomasin Mackenzie (The Power of the Dog), James Norton (Grantchester), and Bill Nighy (The Man Who Fell To Earth) as “test-tube baby” trailblazers Jean Purdy, Robert Edwards, and Patrick Steptoe, won’t let us forget for a second how momentous their scientific breakthrough is and how relevant its social pushback is for us today.

The film trusts its audience not one iota to make these extratextual connections themselves,* with every shred of nuance about the gendered process and hierarchy of the IVF experiment spelled out in dialogue and close-ups of frowning, frustrated faces contemplating the weight of their work. The miscast actors playing stock biopic characters make the artistic hollowness of the project all the more damning.

*(Considering the election results, perhaps understandable. -Ed.)

Though well-intentioned and sometimes effective, Director Ben Taylor’s film, though well-meaning and occasionally compelling, becomes impressive in its commitment to roteness. Joy is a movie made entirely out of overtones, of invitations to nod about the significance of this moment in British history and how the resistance it received hasn’t changed since the late 1960s. It feels entirely constructed out of the short recreation vignettes you see in a made-for-TV docudrama in between actual documentary storytelling.

In 1968, nurse Jean Purdy obtains a laboratory post in Cambridge just before Edwards’ ambitious and heavily criticized IVF trials begin – but the pair of them need the maverick (or, depending on who you ask, over-the-hill) gynecologist Steptoe to face the science’s technical challenges. We meet Steptoe in a typical biopic fashion: disrupting stuffy lectures by claiming his superior methodology and being derisively dismissed by the lesser medical community. Just like they’re putting together a casino heist, Edwards and Purdy need this unorthodox talent (to this day, Steptoe is considered a pioneer in gynecologic laparoscopy) to make headway in their shabby, underfunded Oldham research lab.

Just like One Life, another uninspired British film about inspirational British history, there are rote pleasures in seeing a significant achievement unfold in microcosmic, procedural movements, and plenty of the extended lab work sequences tick along with unremarkable but not unpleasant energy. But Joy’s casting missteps blunt the bumbling British charm of the story. McKenzie is an accomplished young actor, but she’s not suitable for the bubbly, abrupt, and flighty character; her process is far too clipped and internal, and she only truly succeeds when Purdy tries to cope with a complicated personal life with avoidant and indecisive behavior.

As the socially clumsy but always affable Robert Edwards, Norton fares a bit better – but his thickly performed Yorkshire accent and borderline-Nutty Professor energy are frequent reminders of how constructed and artificial this “based on a true story” film is. Nighy escapes unscathed as the cranky but accomplished Steptoe, but only because the role feels tailor-made for his wry, skittish comedic chops, not because he’s bringing anything new to the table.

Joy convincingly but not rousingly depicts the church’s resistance to how IVF proposes disruptions to natural conception in Purdy’s tested and ultimately tragic relationship with her devout mother (Joanna Scanlan) but could use more of the astuteness of a scene where the scientists are denied a grant from the Medical Research Council. The board’s reluctance to fund Edwards, Steptoe, and Purdy’s work indicates the broader skepticism of reproductive science beyond religious ideology.

Radical research undermines the authoritarian, conservative power that so many academic and scientific bodies rely on instinctively, and you don’t hold onto rigid power structures by yielding groundbreaking medical agency to half the nation’s population – who those in power already benefit from oppressing in different legal, medical, and financial ways. This is Joy’s best scene because it’s historically sharp and because our scientific characters’ frustration and resignation make their work’s emotional stakes feel urgent and wide-ranging.

What’s less impressive is how often screenwriter Jack Thorne (story credits are shared by Rachel Mason, Emma Gordon, and Shaun Topp) turns to reductive and misguided theming about the importance of motherhood. Purdy’s relationship with the trial subjects primarily serves to underline her relationship with pregnancy – she explains that her fertility has been adversely affected by severe endometriosis, a debilitating and still underfunded condition many women and trans people are expected to live with. In Joy, none of Purdy’s symptoms ever make it to the screen – her condition is used exclusively to complicate her relationship with motherhood.

Throughout Joy, the unsubtle, insistent script (characters say “choice” is the essential thing about two dozen times) hammers home the revolutionary science of IVF by stressing every woman deserves to give birth and raise a child, treating motherhood as an almost sacred end goal for medical technology. It reinforces the essentialist and conservative messaging that stood in IVF’s progress in the first place – that women deserve access to procreation and family-rearing because it’s such a unique, incredible thing, rather than completely unobstructed body autonomy because obstructing it in any way is barbaric. It’s a severe oversight that Joy seems too happy to make In its eagerness to play to the broadest, safest crowd.\

Joy is currently playing in limited release in the U.S. The film will debut on Netflix on Friday, November 22, 2024.