Everything to Know About The True Story of 'Mr Bates vs The Post Office'

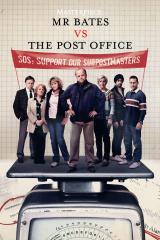

The cast of Mr. Bates vs the Post Office

ITV

Despite sounding exactly like one of those twee English village comedies with ludicrously small stakes and a lot of homegrown British heart, Mr Bates vs The Post Office is about one of the most egregious and calamitous miscarriages of justice seen in the United Kingdom. Masterpiece will run an explainer, The Real Mr Bates vs The Post Office, when the series concludes, but until then, we're here to help.

Between 1999 and 2015, some 900 Post Office workers or partners were convicted of stealing from or defrauding the Post Office because of massive financial discrepancies that appeared suddenly or without reason in their computerized accounts. Post Office Limited, denying that there was any fault in their expensive and widely used computer program “Horizon,” saw to it that hundreds were convicted and more bankrupted themselves, making up the losses that the buggy computer system alleged were their fault.

Decades passed before these workers, known as “subpostmasters,” built momentum enough to challenge the Post Office’s allegations against them, as the company remained obstinate in its stance that Horizon was capable of any faults. This, as Mr Bates vs the Post Office reveals, was a massive lie, and the extensive reach of such a lie makes it extraordinarily difficult for the victims to truly be compensated. But for those who are just now hearing of what went down, here’s a brief explainer.

The Post Office is a private company in which the British state is the sole shareholder—a distinction that sounds like it allows for checks and balances but, in reality, does little of the sort. For centuries, the Post Office has also been able to privately prosecute—as in, without going through the government agency Crown Prosecution Service—its employees and partners. This is one reason why the convictions, fines, and prison sentences handed out to subpostmasters happened so quickly and with little resistance.

Hang on, what is a “subpostmaster”? Very few British post offices (where a community can buy stamps, send parcels, etc) are actually owned and operated by the Post Office – they’d need to run over 11,000 branches across the country. In fact, they run 1% of the total branches; the rest are run by franchise partners and independent branch managers, sometimes inside a convenience or grocery shop. These are subpostmasters, and within the contract they signed with the Post Office when they first began operations, they are legally responsible for making up the deficit in their accounts. Again, this sounds fine if the losses are a couple hundred until a situation arose where fake losses were paid back in thousands of pounds at a time, which became Post Office profit.

So what the heck happened with Horizon? It’s basically advanced accounting software (advanced for the year 2000…) that is meant to update, facilitate, and standardize all subpostmaster activities for the modern era. The software, provided by Japanese corporation Fujitsu (who have a base in the UK), was riddled with bugs that would result in shortfalls magically appearing in subpostmaster accounts. This would be less of a problem if Fujitsu or the Post Office ever openly admitted that they were acting upon flawed data when they came after their least protected traders, but the deceit went further. To many of the subpostmasters complaining about Horizon bugs, the Post Office maintained they were isolated issues that hadn’t been reported by others – a bare-faced lie.

It gets worse. Post Office maintained that no one but subpostmasters themselves had access to their Horizon accounts – there was no remote access overseen by or known to Post Office Limited or Fujitsu. As the thrust of Mr Bates’ drama explores, this was also untrue – Fujitsu had the ability to remotely enter an individual’s account and manually change the numbers. The Post Office denied this until they were forced to admit it, burying evidence and delaying handing over documents to make the sub-postmaster legal case as insubstantial as they could possibly make it.

Some form of justice did prevail. After half-hearted and deliberately misleading promises to subpostmasters affected by their ironclad contracts and the unjust prosecutions, the Post Office set up mediations that collapsed when it became clear they weren’t serious about meeting people halfway. Alan Bates, who had led community gatherings of victims for years, led a civil case against the Post Office in the High Court, and the eventual settlement was a total of £58 million – but after legal fees, the subpostmasters were left with £12 million to share among 555 plaintiffs.

By this point, many accused and convicted subpostmasters had passed away; some even had taken their own lives. The emotional distress of the victims was enormous, but from the civil case, hope sprung. Convictions started to be quashed (so far, one out of nine), and more came forward knowing their testimony would be heard. Mr Bates vs the Post Office was another major milestone – its huge viewership and outrage felt by audiences pushed the miniseries and the recent events it depicted to be discussed in parliament in record time.

Still, the extent of the tragedy has been somewhat obfuscated by the series. While CEO Laura Vennells (whose royally-granted CBE was revoked earlier this year after the premiere) receives most of the blame, former chief executive Adam Crozier led the company during a vast amount of accusations and prosecutions. He then did a stint (2010-2017) of being the chief executive at ITV, the network that produced and broadcast Mr Bates vs the Post Office. He is, as you might have guessed, not mentioned in the series.