How British Pantomime Became Such a Holiday Tradition

Pamela Raith

Not to like pantomime, the journalist Leigh Hunt declared, is not to like love: pantomime is a curious blend of continental and British traditions. The raw energy of music hall, the sauciness of Victorian burlesque, the crazy chase of the harlequinade, the acrobatic power of John Rich, the archetypal plots of commedia. All these elements have shaped the pantomimes we enjoy today. The story of pantomime is a story of transformation and endless adaptation. Professor Jane Moody. Read more.

Happy holidays, and here’s your guide to the art of the English pantomime (Panto). First, it’s nothing to do with Mime (i.e. creepy people silently trying to escape imaginary cubes)—although it may share some of the same roots.

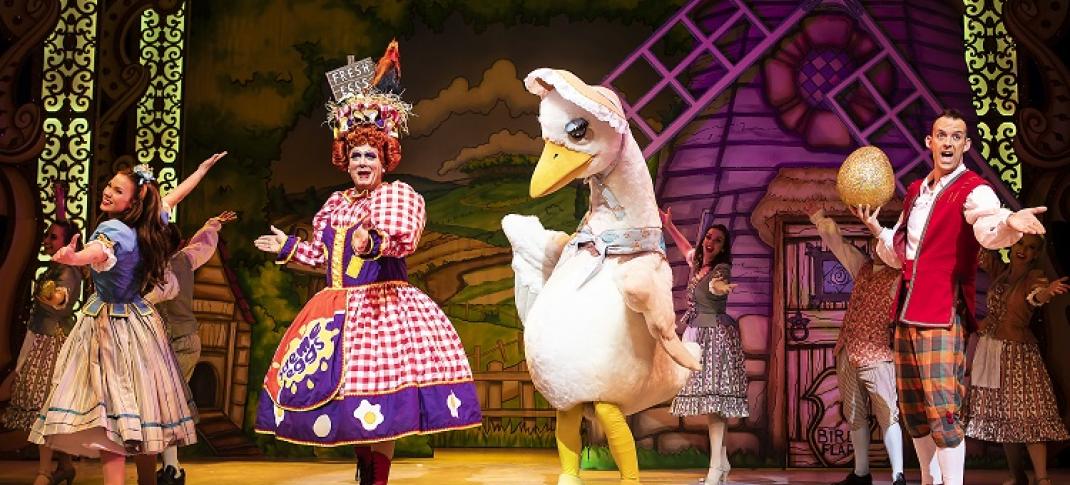

Panto is performed in everything from top city theaters to village halls in British-speaking communities worldwide. They’re family shows built around a familiar story featuring song, dance, political satire and commentary, audience participation, and lashings of double-entendres (which the kids aren’t supposed to understand). They are not at all PC. And, oh yes, The cross-dressing. Remember:

- The Principal Boy is a girl.

- The Principal Girl is a girl.

- The Dame is a man.

So how on earth did Panto evolve? We have to go back several hundred years to the Commedia dell’Arte, a street theater that originated in Italy and spread all over Europe. Much of the appeal was that the stock characters were always recognizable—Pantalone, an old man, rhw servants/lovers Arlecchino and Columbine, and a clown. The storylines generally revolve around the servants getting the better of their masters, and true love winning the day. While it existed as street art it was also taken up by the very aristocrats whom it satirized and became part of courtly entertainment.

Meanwhile, in eighteenth-century English theaters, lengthy, lavish productions always closed with a farce, which involved chases, slapstick, music and dance, featuring stock characters of lovers, clowns and servants, and featuring the artists from the main event of the night. Technological advances such as sliding flats for scenery, and hydraulics to raise and lower parts of the stage, opened up new possibilities for grand productions

It was only a matter of time before the Harlequinade—the creation of John Rich (1692-1761), took over the entire evening. Rich himself started as an acrobat and mime—he didn’t sing or speak on stage but he was a fine dancer, and made the role of Harlequin the clown his own, at his theater in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Harlequin wore a distinctive spangled suit and carried a magic weapon, which he used to slap the scenery to indicate a scene change, thus bringing about the term “slapstick.” After a very successful run of the Beggar’s Opera, the greatest hit of eighteenth-century England, Rich made enough money to open a theater at Covent Garden (the first on the site). His Harlequinades were wildly popular although criticized for bringing down the tone of serious theater.

Rival theater owner David Garrick at the Drury Lane Theater was a critic, but smart enough to realize that Rich was onto something (and was stealing his audiences), and began to produce similar theatrical entertainments of his own, but only at Christmas, thus retaining high cultural standards for the rest of the year.

The Pantomime evolved quickly. Beginning in 1789 with a production of Robinson Crusoe, there was more emphasis on plot, although shows were generally based on fairy or folk stories familiar to the audience—Cinderella, Aladdin, Babes in the Woods. In the 1789 Robinson Crusoe the young son of a theatrical immigrant family, Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837), made his debut as the Clown, a rude, ravenous character who delighted audience with his greed, anarchy, and contempt for authority. Grimaldi's catch-phrase--Here we go again!--is still used in Panto today.

Later in the century music halls became wildly popular as a form of entertainment, variety shows that offered audiences laughs, dance, music, acrobatics, and girls in tights, and two more important traditions were established. Dan Leno (1860-1904) first appeared on stage as a Clown at the age of five, but went on to become the most popular and beloved Dame of his generation—the stock female character, usually the mother of the hero, performed by a male actor. It also became traditional in this period for the Principal Boy to be played by an attractive young woman. Pantos became wildly popular, involving elaborate spectacles and special effects, and huge casts, but it wasn’t—and never has been—entirely respectable:

The Drury Lane pantomime…is a symbol of our nation. It is the biggest thing of its kind in the world, it is a prodigal of money, of invention, of splendour, of men and women, but it is without the sense of beauty or the restraining influence of taste. It is impossible to sit in the theatre for five hours without being filled with weary admiration. Only a great nation could have done such a thing; only an undisciplined nation would have done it. The monstrous, glittering thing of pomp and humour is without order or design; it is a hotch-potch of everything that has been seen on any stage. The Star, 1900.

Although diluted, the genre continues to evolve and is the sellout event of many amateur theatrical groups. Starring roles are now often taken by celebrities from TV soaps or popular music, and the Principal Boy is not always a girl. But the raucous humor, rudeness, subversiveness, and sheer vitality of the genre continue to entertain. Have you ever been to a Panto or even taken part in one?

With the last word, here’s a memorable Widow Twankey in his time, Sir Ian McKellen, on the appeal and fun of the Panto: