The Brits Are Coming: The History of The Battle of Bladensburg

The War of 1812 is both fascinating and confusing. It’s not really even clear which side won—either could claim it as a victory. Certainly it changed America, persuading the government that both a standing army and navy were necessary and establishing our country as a world player. It forged a stronger identity for the new republic, and provided us with a national anthem. In European history, it’s overshadowed by the Napoleonic Wars. (1812? That’s when Napoleon invaded Russia!)

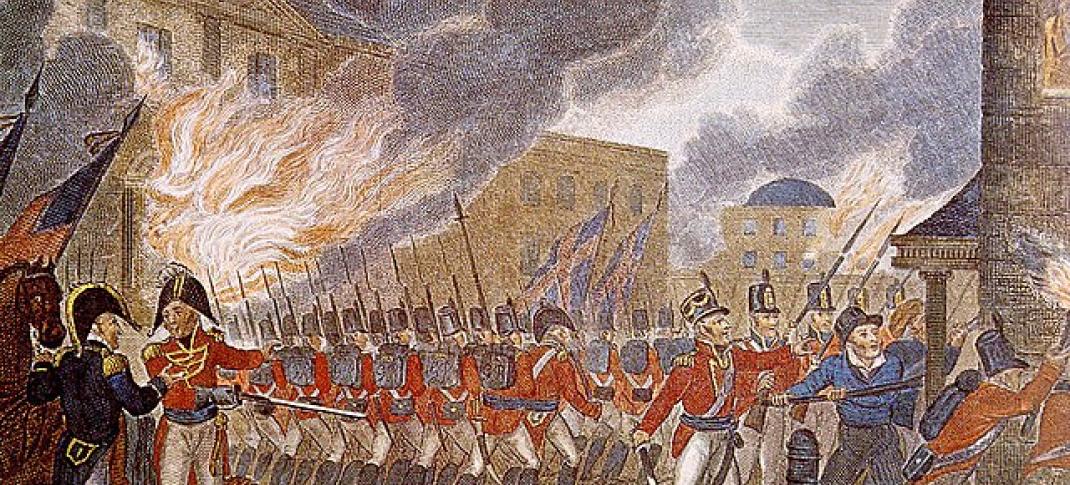

Here in the States, we all know about the burning of Washington by the British in 1814, and the decisive Battle of New Orleans that ended the war a year later. But the prelude to the invasion of Washington, the Battle of Bladensburg, is less well known, representing as it does an enemy invasion and victory on American soil.

In other words, it was not our finest hour. (Nor was it that of the British, for that matter, whose destruction of Washington was roundly condemned on both sides of the Atlantic).

We have … learned that the English are going to send a considerable force here. Their ships are already in our Patuxent [River]. They have burned several houses and tobacco warehouses. I don’t know how it will all end. June 24, 1814

Since I started this letter we have been in a state of continual alarm, and I now have time to write only two or three lines to ask you to tell Papa that we are all still alive, in good health, and I hope safe from danger. I am sure that you have heard the news of the battle of Bladensburg where the English defeated the American troops with Madison “not at their head but at their rear.” From there they went to Washington where they burned the Capitol, the President’s House, all the public offices, etc. During the battle I saw several cannonballs with my own eyes … At the moment the English ships are at Alexandria which is also in their possession. I don’t know how all this will end, but I fear very badly for us. It is probable that it will also bring about a dissolution of the union of the states …. At present my house is full of people every day and at night my bedroom is full of rifles, pistols, sabers, etc. August 30, 1814

Letters from Rosalie Calvert to her sister from Mistress of Riversdale: The Plantation Letters of Rosalie Stier Calvert, 1795–1821, Margaret Law Calcott, ed. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

The War of 1812 lasted only a few years, but involved a vast geographic area and a total of four nations (not just America and Britain) with a relatively small number of combatants: Canada, at that time a British colony, resented becoming involved in a war which had nothing to do with them; and the visionary Shawnee warrior Tecumseh saw the war as an opportunity to create an alliance of Native American tribes and prevent American expansion westward.

As for Britain and America, things had been coming to a slow boil for years. Under Thomas Jefferson’s presidency (1801–1809), pressure was put on America by both Britain and France to become a favored ally and sole trade partner (and, it was implied, to take a side in the Napoleonic wars). Jefferson’s solution was to ban all trade with either country and allow Americans to trade only with Russia instead, starting a massive smuggling industry. As yet, America had no standing army, relying on local militia, and its relatively new navy, with only a handful of ships, was pretty much neglected. Worse yet, the British had no compunction whatsoever about seizing any American ships and their cargoes and, in a move that particularly upset Americans, impresing crew members to serve in the Royal Navy.

When President James Madison declared war in 1812, it was out of desperation, with the country facing bankruptcy. For the Brits, it was unbelievable, if not laughable, that their former colonies should challenge the greatest power in the world. Yet when American ships had the nerve to seize British ships in the Thames Estuary and the English Channel, it was made clear that the upstart young republic meant business.

Although the early main thrust of the war was in Canada, the Royal Navy had almost complete control of the eastern seaboard by 1813, including the vitally important Chesapeake Bay. As well as burning and looting, they also encouraged slaves to escape and join the Navy for the promise of freedom, and it’s estimated that about 4,000 did so. The British were well aware of the psychological impact that African-American sailors would have on a mostly all-white enemy.

Things escalated in 1814 when Napoleon was exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba, freeing up British troops and ships. On August 19, General Robert Ross landed in Benedict, MD, on the Chesapeake Bay and marched inland with 4,500 troops. It wasn’t clear to General William Winder, commander of the American militia, whether the British were heading for Washington or Baltimore. The port town of Bladensburg was the key for defense to both cities (about eight miles from the capital and fifty from Baltimore). President Madison, who had attended the troops before the battle, was safely hustled away before the battle began on August 24th, 1814. He escaped later in the day to Virginia, and First Lady Dolley Madison, despite the desertion of her guard of honor, stayed in their house long enough to pack and save valuables including the famous portrait of George Washington.

The American militia numbered about 6,500 but they were poorly trained and no match for the British troops, known as "Wellington’s Invincibles," battle-hardened veterans who had fought Napoleon. The British, as well as presenting a terrifying appearance, had no artillery except for Congreve rockets, a recent invention new to Americans. Although these rockets were famously inaccurate, they produced a great deal of noise, smoke, and alarm. In addition, the placement of American troops was faulty, not allowing different units to communicate effectively. Here's a very nifty animated map of the battle.

Remember, too, that it was a typical hot Maryland August day, with very high humidity and temperatures in the 90s, and typically the troops would have refreshed themselves with rum or other alcohol. In all, it was a disaster that sadly became known as the Bladensburg Races.

Commodore Joshua Barney’s Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, a company of freedmen, were in charge of the American artillery and held steady as others panicked. One of these men, an escaped slave and self-proclaimed freedman, Charles Ball, reported:

I stood at my gun, until the Commodore was shot down, when he ordered us to retreat, as I was told by the officer who commanded our gun. If the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, could have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs.

The Americans scattered, and the British marched into an almost deserted, undefended Washington where they broke into the President’s House and found the table set for forty, anticipating an American victory celebration. After drinking, they piled the furniture up and set fire to the house. Other government buildings were set on fire, with the exception of the Patents Office, which in true enlightenment spirit, was spared because it contained intellectual property. The U.S. Navy itself set the Navy Yard and two newly built warships on fire to prevent anything falling into British hands.

Probably the savagery of the destruction was in retaliation for the American burning of York, Canada’s capital at the time, and Toronto, but it shocked the world, particularly England.

For more information you can read about the battle and view maps at battlefields.org. A few years ago PBS (in partnership with WNED and WETA) presented a full-length documentary, The War of 1812, available online with essays on the historical background and information on the making of the film.

And if you’d like to see a reenactment of the Battle of Bladensburg, there’s one taking place on Saturday August 24, 2019, noon to 4 p.m. at Riversdale House Museum, the same house owned by Rosalie Calvert whose letters so dramatically describe the battle and its aftermath, just a couple of miles away from the battlefield. You can meet historical reenactors representing the militias, Navies, and British Army, see demonstrations of drills and cannons, and tour Rosalie's house.

Had you heard of the Battle of Bladensburg? And how important do you think the War of 1812 was?