A Fraying Cromwell's Hold Slips as 'Wolf Hall' Endgame Begins

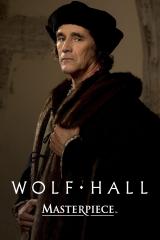

Mark Rylance and Ellie de Lange in "Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light"

(Photo: Masterpiece)

Historically speaking, Thomas Cromwell is not a man who is easy to know. While many historical records of his public actions survive, we know relatively little about his private life. It's why the Wolf Hall franchise (both the television series and Hilary Mantel's trilogy) is so fascinating, offering Cromwell the depth he is often denied by history, for both good and ill. And Wolf Hall: The Mirror & the Light's fourth episode gives Cromwell a uniquely tragic sort of interiority just as the shape of his doom begins to come clear.

The Jenneke of the episode's title is a fictional construct, a character created by Mantel to stand in for an illegitimate child Cromwell was rumored to have. However, it should be noted that no historical evidence of such a child exists. In the world of the story, Cromwell's daughter has revealed herself in an attempt to save her father. Having heard he was in danger from the northern rebels, she wants to spirit him back to Antwerp and safety. But in the larger arc of Cromwell's story, Jenneke (played by Ellie de Lange) is as much a concept as a person: an intriguingly personal "what-if" scenario about the life he could have had if he'd made different choices as well as hope that he might be able to one day fashion a life for himself that's free of Henry's chains.

It's what his visions of Laude Abbey represent — the possibility of peace. Cromwell has dreams of retiring to the Abbey with his newfound daughter, content to stroll amongst the busy beehives and lush flowers. Jenneke smartly refuses to place herself voluntarily under Henry's control and returns to Antwerp, with her father wistfully watching her go.

Cromwell's illegitimate daughter is one of the children that "Jenneke" focuses on. Jane finally gives birth to the son Henry has upended the world to have, and unsurprisingly, her husband seems to spare her little thought afterward. Her throne is empty as the young prince is presented to his father and the court, but the only person who seems to notice is Cromwell. He's worried, and with good reason: Jane is not well, and when he arrives to visit her, she's retching violently and can barely stand.

Historically, Jane's labor was reportedly difficult, lasting for two days and three nights. However, despite the rough birth, she seemed well enough that plans were underway for her "churching," a religious ceremony in which new mothers were cleansed before being allowed back into court life. Most modern historians believe she contracted childbed fever shortly after Edward's birth, and she died just 12 days later. Wolf Hall's version of events sees Henry with her at the end, though his insistence that he'd "walk to Jerusalem" to save her life rings more than a bit hollow thanks to his interest in adding Mary of Guise to his marriage shortlist what feels like five minutes later.

It is Cromwell who seems most devastated by her loss. He flees Jane's deathbed, though the show leaves it up to the viewer to decide whether he's overcome with emotion or irritated that she's been given Last Rites in a decidedly Roman Catholic style, complete with golden goblets and a giant crucifix. His ill-advised outburst about how he would have done better by Jane had she married him instead indicates the former, as he cites everything from rich foods to cold chambers for her loss.

(This is also a not-so-subtle way of blaming Henry for her death, particularly since he seemed so uninterested in her welfare earlier in the hour.)

Cromwell's outburst after Jane's death is but one of many hints that his iron control is slipping. Sent to interrogate Gregory Pole, he tells Wriothesley that he'll do whatever it takes to secure the legacy of their Reformation in England, even if it means openly opposing Henry. Elsewhere, Bishop of Winchester Stephen Gardiner (now played by Alex Jennings) returns from France with a still-entrenched hatred for his old enemy and a newly firm grasp on the king's ear that grants him enough power to openly accuse Cromwell of murdering Wolsey's enemies.

Then there is the matter of John Lambert. The Mirror & the Light throws this subplot in without giving its story much context, assuming its audience is either familiar with the story of early Protestant martyrs or at least willing to Google them. A humanist theologian who was burned at the stake for heresy in 1538, Lambert openly denied the doctrine of transubstantiation (that Jesus is present in the bread and wine used during communion) and insisted that women should be able to teach and priests to marry.

("But isn't that what Protestants generally believe?" you might be wondering. A quick bit about religion — at this point, Henry had broken with the Roman Catholic Pope and declared himself the head of the Church in England. But he did this more for power and personal gain than questions of faith.)

By disavowing Rome, Henry got the divorce he wanted and could amass vast wealth for the Crown by dissolving the Catholic monasteries and claiming their lands and riches himself. However, in terms of belief structure, Henry's church was much closer to traditional Catholicism than the strains of Protestantism (Lutheranism, for example) practiced by many in Europe at the time; Henry had precious little interest in changing that.

Henry wants Cromwell to shred Lambert and his heretical beliefs publicly since he's used to Cromwell being his attack dog in all things. (With Thomas More dead, Cromwell was considered The Lawyer in England.) Cromwell swallows the truth of his own beliefs, supports the king, and presumably lets Lambert go to his death. However, his guilt over it later is new. Given all we have seen of Cromwell, his discovery of concepts like "a conscience" and "a sincere personal belief system" feels a little convenient. But whether he can see Henry's affection turning or knows that England's nobles are still waiting to bring an upstart down, he's suddenly behaving like a man who knows he's on borrowed time.

He doubles down on the idea of his reformation, vowing to Wriothesley that if he can just have a year or two, he'll see it complete, and the changes so entrenched in England they won't be able to be undone. He's ready to take on the remaining great Catholic families (largely Plantagent-adjacent holdovers like the Poles and Courtenays) even as he negotiates a new queen for Henry of a determinedly Protestant background.

We're suddenly seeing a man desperate to prove to himself, to the Dorothea that haunts his nightmares, even to Wolsey's ghost, perhaps, that there is more to him than naked ambition, that there is faith and truth in Cromwell, no matter what people may have told the man he loved best. It's a dream he'll lay down his life for, in the end, and the fact that he can so clearly see it coming is perhaps the hour's greatest tragedy of all.

Wolf Hall: The Mirror & the Light airs on most local PBS stations and streams on the PBS app weekly on Sundays at 9 p.m. ET. All episodes are available for PBS Passport members and the PBS Masterpiece Prime Video Channel to binge before their on-air broadcast.