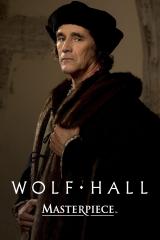

'Wolf Hall' Costume Notes: "Mirror" & "Light" Dress Henry Up & Cromwell Down

Damian Lewis and Dana Herfurth in "Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light"

(Photo: Masterpiece)

Wolf Hall has concluded, long live Wolf Hall in all its iterations! The final two episodes of the miniseries present viewers with a steep downward slope for our equally flawed and compelling protagonist as one thing after another goes wrong for him. Anna of Cleves’s arrival and all too brief marriage to Henry VIII are a nearly unmitigated disaster and weaken Cromwell at a perfect moment for the loathsome Stephen Gardiner and the Duke of Norfolk to team up and bring him down.

As Cromwell’s sphere of influence and chances of survival shrink and dwindle to nothing, his king and queens carry on largely as they always have, in luxurious fabrics and colors forbidden to others.

I dislike Henry VIII as much as anyone who isn’t one of his wives. However, it is undeniably sad that a born actor was prevented from pursuing a life on the stage and instead was unleashed on the world as a self-obsessed and increasingly cruel monarch. As we saw in the ball where he performs anonymously (or so he thinks) as a Turkish dancer, for Henry, to be in motion was to be happy. Losing the famed athletic vigor of his youth so precipitously, leaving him in chronic pain with an injury that could not heal, must have been a terrible blow.

The Lamentable Tragedie of Thwarted Theatre Kid Henry VIII

Damian Lewis summons a sweet, even childlike, note of delight in his performance of Henry’s ill-fated plan to surprise Anna of Cleves (Dana Herfurth) upon her arrival in England, lending a note of poignancy to a scene otherwise designed to elicit second-hand mortification and dread in viewers. He thinks he’s going to delight Anna and make an irresistibly charming first impression on a woman who Cromwell has described as extremely unworldly and sheltered, wholly ignorant of what her court would consider scandalous behavior on the part of the king.

Henry pays no mind, rummaging through his trunks of costumes — another minor key note in what he somewhat desperately thinks of as a peppy little concerto unmarred by obvious flop sweat — and showing Wriothesley (Harry Melling) and Cromwell the costumes he might wear “to nourish love…to surprise her and gladden her heart” by visiting his fiancée in disguise. As he reasons aloud that “a bridegroom must have his caprices”, and that his advisors can have no fundamental understanding of the matter because they weren’t born to nobility and Cromwell in particular is “no adept at courtship”, Henry makes his way through several disguise options: Russian nobleman (“with great fur boots!”), shepherd, or even one of the Magi.

The items he holds up for their assessment aren’t in the style or degree of formality of his usual garb, but some are rendered in fabrics that seem even more luxurious than what he typically wears. One robe is made of floral silk brocade in celery green, featuring an all-over design of pale pink peonies. Its lining is bold cinnabar red, with stylized florals in maroon and gold-leaning beige. The robe he would wear as one of the Magi is another lavish silk brocade, this time in a sunny gold, with “oriental” motifs, a sage-colored lining, and tipped from collar to hem and at the cuffs in a lush brown fur. They’re all magnificent and each probably costs more than Wriothesley makes in five years.

Cromwell’s suggestion that he go as a nameless gentleman of England hits the mark; unfortunately, such a costume doesn’t seem to exist in Henry’s trunks, but I think a reasonable mental image would be something like Rafe Sadler’s usual look. His clothes are well-made, quite sober, and include just a pop of color here and there – something along the lines of the rich green of his elbow-to-wrist cuffs in Episode Six.

Before we move on to other garments, dear readers, if you’ll be so kind, please indulge a slight detour into character analysis outside of costume design: having seen Cromwell’s ability to (85% unintentionally) charm Mary Boleyn, the Lady Mary, the late Queen Jane, and Jane’s sister Elizabeth before her eventual marriage to his son Gregory, it seems as though the man has game to spare.

On the other hand, it’s unsurprising that Henry would underrate Cromwell as any kind of suitor because he underrates his advisor’s chief asset: his sincere interest in what women think and have to say. A clever, wealthy, powerful man who pays attention to and is curious about women’s actual thoughts? A rare and precious jewel, even in the 21st century!

Next Queen Up: Katherine Howard

Notably, we get an eyeful of Henry’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard, before we even glimpse his fourth. Anna of Cleves’s ladies-in-waiting arrive in advance of the future queen, and are all being readied in the gowns they’ll wear as attendants at their lady’s wedding. They’re a sea of ivory and gold, some without hoods or veils, and with their hair arranged in sweet-looking braid crowns. Into this scene of gleaming sartorial innocence arrives the Duke of Norfolk (Timothy Spall), with another of his nieces, Katherine (Summer Richards), on his arm. The contrast between her gown and those of the young Germans could not be more stark – not in style, but in color.

Without rewatching the entire season from start to finish, I can’t say this with absolute certainty, but I’m confident that this is the first time we’re seeing any female character in head-to-toe royal blue. The color stories of this season have primarily revolved around shades of red and gold, and the characters themselves have all reached adulthood. Both Lady Rochford’s comments about Katherine’s extreme youth and simplicity (“her mouth’s always hanging open”) and the luxury of her gown highlight what a novice she is at court life. Like the king, she looks like she loves to play dress-up, wearing jewels that once belonged to Anne Boleyn and a gown that’s the Tudor equivalent of a special first day of school outfit.

The style of the gown is precisely what we expect to see on a respectable young lady of the court. Still, even with its square neckline, long, voluminous sleeves that widen dramatically at the wrist, and use of both solid and tone-on-tone damasks, it can’t make her look more than a year or two older than her actual age at the time, which was no more than 17.

Bridegroom Changing Things Up

The final episode of Wolf Hall doesn’t feature any truly remarkable new-to-us costumes. Still, it does showcase some notable moments, including charges that Cromwell violated sumptuary laws by wearing purple and sables. First, let’s look at Henry’s wedding ensemble for his marriage to Katherine Howard. After three entirely gold-forward ceremonial looks, this is a Bridegroom Changing Things Up, making purple the color of the day. His deeply saturated purple silk doublet, featuring complex botanical motifs in gold, a skirt of gold brocade, and a snowy white fur-collared robe, is all very kingly. However, I wonder if the purple is meant to suggest that he’s trying too hard. This is his fourth marriage in seven years, and by this point, even he knows his situation is desperate.

For her part, Katherine is Keeping It Classic, shown being readied by her ladies, letting them all know in uncertain terms that they’re irritating her and in at least one case, sticking her with a pin meant only to secure an oversleeve. Kudos to Richards, whose entire performance is silent across her two scenes, for putting across exactly who this poor girl was. Where Anna was almost heroically impassive and skilled at schooling her face to a nearly disconcerting smoothness, Katherine’s face is a window thrown wide open to her feelings. Her wedding dress, like Jane’s and Anna’s before her, is an ivory-and-metallic affair, with a golden fabric that almost looks embossed, its allover texture catching the light beautifully with each of her movements.

Finally, a shout-out to the beekeepers’ masks of Launde Abbey, where Cromwell sends his consciousness after paying off and reassuring the executioner that there’s no hard feelings. The beekeepers’ totally blank facelessness looks so scary at first but on reflection, the rustic simplicity of the woven wicker and the anonymity the masks provide suggest something that I think Cromwell sought in his final moments: the quietude and relief of not being perceived or known, and the luxury of living out his remaining days as a well-off retiree enjoying the literal fruits of his years of labor.

Both Wolf Hall and Wolf Hall: The Mirror and the Light are now streaming with PBS Passport on the PBS app and via the PBS Masterpiece Prime Video Channel.