1066: The Only Date All Brits Know

Think Game of Thrones. Instead of the Iron Throne, we have the throne of England up for grabs, three candidates, and a lot of bloodshed.

England just before the Norman conquest is just that—it doesn’t include Wales or Scotland yet, and was technically only conquered by Vikings a couple of generations ago and still suffering frequent coastal raids. It’s divided into earldoms which answer to the king. but the earls’ estates are further divided into Hundreds (a collection of one hundred households with a court to settle local matters), a name that still exists within some land descriptions. London is the center of trade, and King Edward (later sanctified and known as Edward the Confessor) has begun to build the Palace and Abbey of Westminster, a mile downriver, possibly planning to move the royal seat from the current capital, Winchester.

But Edward has no direct heirs. The correct procedure in this case should pretty much mirror that set out by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. We anticipate a not particularly star-studded event in which the leading nobles of England elect the new king from among their peers, just like the Academy Awards. Except this doesn’t happen. But as he's dying in 1065, shortly before his death, Edward wakes to tell of a dream where two monks appeared to tell him England is destined for war and chaos. How right he is.

Three warlords are determined to claim the throne and so this The Bachelor equivalent of 1066 presents our candidates:

- Edward’s brother-in-law and right-hand-man Harold Godwinson. who claims that the late king appointed him his heir, but apparently forgot to mention it to anyone else. Interests: brutal warfare.

- William the Conqueror, a.k.a William of Normandy, a.k.a. William the Bastard (which he was in all definitions of the word). He claims that in 1051 he visited his distant cousin King Edward, who named him the heir to England. Furthermore, he says Godwinson swore an oath that he would support William’s claim to the throne. You have to wonder why, but at that date Harold was not as tight with Edward as he later became. Interests: brutal warfare and eating.

- Harald III, King of Norway, whose grandfather was the last Viking to invade England, which gives him a claim of sorts, or at the very least a family tradition to follow. Named Hardrada, or hard leader, and yes, he too really enjoys brutal warfare.

After Edward’s death on January 4, things move very quickly. On January 6 the Abbey of Westminster hosts a double billing, a special episode of Dancing With the Stars where Harold Godwinson wows with his slick moves from tomb to crown--the royal funeral and a coronation on the same day.

Harold is now King of England and the richest man in Europe. But for how long?

Shortly afterward, Harold exiles his brother Tostig, Earl of Northumbria. Tostig approaches William of Normandy looking for a possible collaboration, and is apparently rebuffed. However, Harald Hardrada is very interested, and starts sharpening his Viking battle ax.

As the year progresses, a terrible omen appears in the sky, an appearance of what was later named Halley’s Comet. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of manuscripts from various religious houses around the country, records:

At that time throughout all England a portent such as men had never seen before was seen in the heavens. Some declared the star was a comet, which some called the “long haired star:” it first appeared on the eve of the festival of Letania major, that is on the 24 April, and it shone every night for a week.

In September, Harald Hardrada’s three hundred warships sweep down the east side of England, sail up the River Ouse, and take the city of York. Tostig meets him there with recruits from Scotland and Flanders, bringing the total invading army up to about 9,000. They are met by King Harold and his army of 12,500 at Stamford Bridge five miles east of York. On September 25, 1066, Harald and Tostig are killed along with 8,000 of their men, giving a decisive victory to King Harold.

Meanwhile William of Normandy has been preparing for invasion and war. He is able to do what both Napoleon in the nineteenth century and Hitler in the twentieth failed to do—ship arms, equipment (including warhorses in this case), and men across the English Channel, which, while only twenty-two miles at its narrowest point, is famously unpredictable. He lands at Pevensey, Sussex, days after Harold’s victory in the north. From William’s point of view, Harold has broken an oath made before God, and this serious sin gives him the moral authority to take the throne.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives a brief, eloquent description of what happened (translation below and if you listen carefully you will recognize many of the words).

Then King William came from Normandy into Pevensey, on the eve of the Feast of St. Michael, and as soon as they were fit, made a castle at Hastings market-town. Then this became known to King Harold and he gathered a great raiding-army, and came against him at the grey apple-tree. And William came upon him by surprise before his people were marshalled. Nevertheless the king fought very hard against him with those men who wanted to support him, and there was a great slaughter on either side. There were killed King Harold, and Earl Leofwine his brother, and Earl Gyrth his brother, and many good men. And the French had possession of the place of slaughter, just as God granted them because of the people's sins.

What happened at the actual battle itself is unclear. We don't even know what size army William brought with him. His chaplain, William of Poitiers, gave the ludicrous number of 60,000 men, topped later in the century by two claims of 120,000. Various contradictory accounts sprang up within the next century, biased by the viewpoint of the Norman or Anglo-Saxon writers. One of the most famous myths is that Harold was killed by an arrow in his eye, but at least three different and equally gruesome accounts of his death exist.

It’s not even clear where the battle took place, although Battle Abbey, built shortly after the invasion purports to mark the spot of Harold’s death at its high altar. The present town of Battle, including the Abbey and the battlefield, are about five miles from the town of Hastings, where Foyle’s War was set, with Michael Kitchen as DCS Christopher Foyle in another time when another invasion seemed imminent.

The reference to the apple tree in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is thought to refer to Senlac Hill, where Harold and his army purpotedly made their last stand. In 2013, BBC-4’s Time Team investigated the site where yearly reenactments have taken place for about the past forty years and found only modern detritus. The landscape was quite different nine centuries ago, with considerably more marshland. The Time Team archaeologists came to the conclusion that the battle probably took place closer to Hastings on what then would have been a strategically strong position on the road leading out of the town.

This assumption is disputed by English Heritage, which sponsors the reenactment, arguing that any archaeological evidence would have been destroyed by the construction of the Abbey. For reenactors’ experiences, you can read a photo essay of the 2018 event.

Harold and his army held the strongest tactical position on the top of the hill, where his elite household warriors locked shields (the famous shield-wall) to protect their king. While the Anglo-Saxon army was mostly infantry, half of the Norman army was infantry and the rest divided between cavalry and archers. Unusually for those times, the battle lasted all day. When a rumor spread that William had been killed, his army retreated, but reformed once more when they realized he was alive. Meanwhile, Harold and his men followed them down the hill, where the Normans surrounded them and consequently won the battle after massive slaughter.

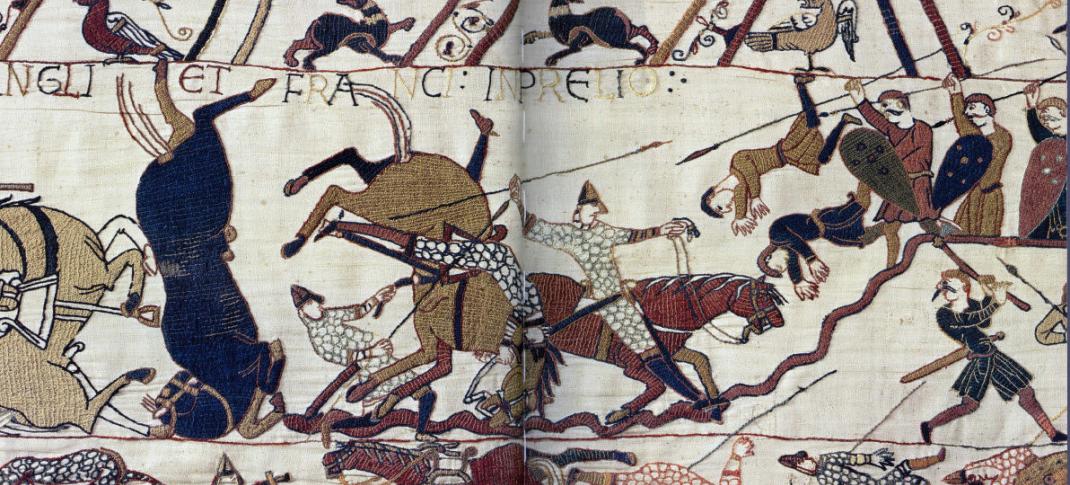

The story of the battle was memorialized in a remarkable piece of art, the Bayeux Tapestry. Commissioned by William’s half-brother Bishop Ordo who fought in the battle (and has a starring role in the tapestry), it tells the story of the entire lead-up to the Battle of Hastings, and is thought to have been made in England in the 1070s. It was rediscovered in 1729 on one of its annual displays in Bayeux Cathedral and is now housed in its own museum (an adjoining museum is devoted to the Normandy Landings of World War II.) Currently, the Bayeux Museum is also exhibiting the Game of Thrones tapestry made in Ireland which tells the story of the first six seasons.

Technically, the Bayeux Tapestry is not actually a tapestry at all. It is embroidered linen, and measures 230 feet long and 20 inches high and represents scenes from the Norman point of view along with commentary. While the tapestry has much to tell us, there are still many unanswered questions, and a repair may be responsible for the myth that Harold died from an arrow in his eye.

Here’s an animated overview of the whole tapestry:

Following the battle, William set out to subdue the whole of England with typical brutal efficiency. Under the feudal system he introduced, all land now belonged to the King, who granted land leases to two hundred Barons, in return for money and armies, and in turn the barons sublet the old Hundreds to Knights. The Knights provided protection and military service, and the class below them, the Villeins at the bottom of the system, provided food and services. Villeins were part of the land; they could not leave their manor and were in effect enslaved.

Trades and industries in the towns, however, were not subject to feudal obligations. William centralized economic power, brought in French merchants and traders, and created French quarters in towns and cities.

The landscape changed as imposing stone castles and religious houses were built over the next couple of centuries. Under Edward the Confessor, there were fifty religious houses, and by the thirteenth century there were over one thousand. Five hundred castles were built, often on the sites of existing houses and graveyards. Rebellions were brutally put down, with the destruction of crops and food as additional punishment during a war of occupation that lasted at least a century.

All in all, it was a fairly miserable time for those at the bottom of the heap, although life probably hadn’t been much better for them under Anglo-Saxon rule. Eventually things settled down after a couple of centuries (which could have represented up to eight generations, given the life expectancy of the times). The languages started merging, and that’s why so many of those words in the excerpts from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle are recognizable. The forbidding religious institutions started to serve the sick and the poor as well as themselves. Intermarriage between Saxons and Normans took place, as differences blurred and interest on both sides in the growing wool industry necessitated communication.

Norman law was created to protect the interest of the rich, but those further down the scale realized that they could use it for their own protection, particularly in disputes with landowners. A turning point was the signing of Magna Carta at Runnymede in 1215, a peace treaty between King John I and a group of rebellious barons, which has gone on to serve as an ideal of democracy, inspiring, notably, our Declaration of Independence.

The name Runnymede derives from two Anglo-Saxon words, runieg (meeting place) and mede (meadow) and was the site of the Witan, the forerunner to Parliament, a significance that cannot have been lost on both sides when Magna Carta was signed.

What do 1066 and the Battle of Hastings mean to you?